Pragmatic Clinical Trials: A Physician’s Perspective on Bridging Evidence and Practice

- Sep 23, 2025

- 10 Min. Read

Pragmatic Clinical Trials: A Physician’s Perspective on Bridging Evidence and Practice

Recently I attended a professional society meeting that opened with a panel discussion on pragmatic trials. During the session, a panel of experts from a variety of backgrounds, including regulatory, industry, and academia discussed the emerging role of innovative pragmatic trial designs to support evaluation of healthcare technologies.

As a physician, I was intrigued. Although I am very familiar with randomized controlled trials, (RCTs) as well as real-world evidence (RWE) studies, I do not have much experience with pragmatic trials. I was inspired by the opening plenary to learn more about how they contribute to real-world evidence and clinical care.

Introduction

The landscape of clinical evidence generation is evolving rapidly, especially with the application of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) techniques. Physicians, regulators, payers, and patients alike are seeking research designs that better reflect the realities of everyday practice while maintaining methodological rigor. Pragmatic clinical trials (PCTs) are emerging as a powerful complement to traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and real-world evidence (RWE) studies. As a physician engaged in evidence generation and evaluation, I see potential for pragmatic trials to play a critical role in filling important evidence gaps that arm front line health care providers and their patients with crucial information necessary to make informed decisions and optimize real-world outcomes.

Defining Pragmatic Trials

Pragmatic trials incorporate randomized designs to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions among diverse patient populations under usual care conditions. In contrast to RCTs, which ask whether an intervention can work under ideal conditions, PCTs ask whether it does work in routine practice. Core features often include:

- Broad eligibility criteria

- Flexibility in intervention delivery (aligned with local standard of care)

- Usual-care comparators

- Outcomes that are patient-centered and relevant to health systems (e.g., hospitalizations, quality of life, safety events)

- Use of routinely collected health data (EHRs, claims, registries)

Strengths of Pragmatic Trials

Pragmatic trials offer several strengths including efficiency, generalizability, and clinical relevance to both providers and payers. Results from PCTs directly inform decisions in real-world clinical practice. By embedding randomization into clinical care workflows, the associated costs are significantly decreased compared to those seen in RCTs. Given the broad eligibility for patient enrollment and the ability to conduct studies in routine care settings, their external validity also surpasses that of RCTs. Additionally, broad eligibility enables researchers to examine effectiveness and safety of health technologies in subgroups of interest that would likely not be included or would be substantially underrepresented in an RCT. Finally, regulators and payers are increasingly using PCTs to guide coverage and access decisions because they better reflect real-world use of the healthcare technologies they study.

Limitations and Considerations

While PCTs present many strengths, they do have limitations. For instance, patients may not always adhere to their assigned care pathway. While cross-over and nonadherence occur in RCTs as well, the likelihood is greater for pragmatic trials because they are less well controlled. Also, data quality relies on those inputting data into EHRs and billing (for claims). This opens up opportunities for misclassification. Additionally, to be accepted by both regulators and payers, the study must demonstrate the robustness of its data, provide prespecified outcomes, and exhibit analytic rigor. Finally, as with any study design, PCTs must provide ethical transparency with respect to patient informed consent and clinician engagement, with patient communication managed carefully. PCTs rely on clinical staff who are less likely to have research experience than those conducting RCTs and thus require more training to ensure high ethical standards are maintained.

Comparison to Other Study Designs

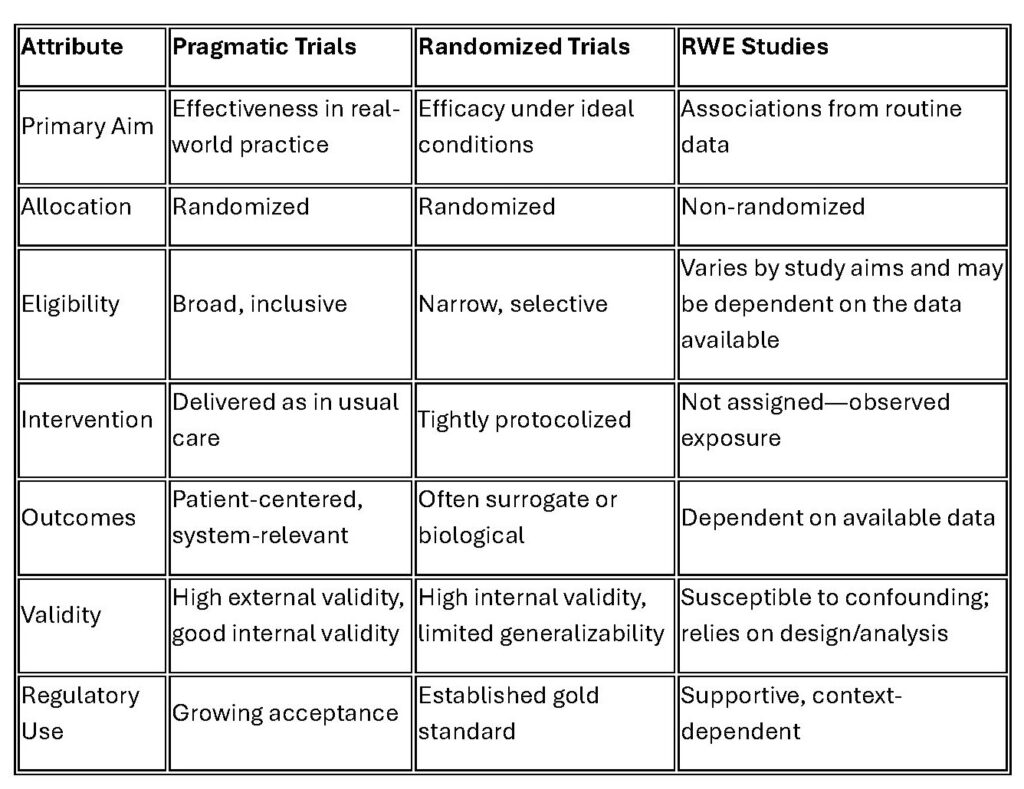

The table below provides a high-level overview of the differences between PCTs, RCTs, and RWE studies.

Potential role for PCTs

Pragmatic trials occupy a middle ground: they retain the strength of randomization while generating insights that are more generalizable to real-world clinical practice and patient populations. In doing so, they generate high-quality RWE that can complement traditional RWE studies and provide decision-grade evidence. RWE studies remain indispensable—particularly for surveillance of safety and effectiveness—but pragmatic trials may enhance evidence generation in real-world contexts.

Example – Primary HPV Testing Implementation in a Large Healthcare System

Recently Chao et al. conducted a pragmatic, cluster randomized trial embedded in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) health system to answer a clinical question related to updated U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines for routine cervical cancer screening. The updated recommendation, based on new evidence, was that effective cervical cancer screening could be performed using hr-HPV testing, with cytology (pap smear) needed only with certain HPV test results, thus requiring fewer tests and achieving significant cost savings. The study was undertaken to determine whether efforts to remove barriers to guideline implementation at various clinical sites in the health system would increase compliance with the new screening approach as compared to a system wide roll-out that did not address potential local barriers in advance.

Researchers randomized 12 sites to study arms, using a locally tailored implementation approach vs. a centralized approach, based on their geographic service area. The study took place over a two-year period. The study cohort included women aged 30 to 65 who presented for routine cervical cancer screening. The women enrolled were part of KPSC’s 4.8 million members from diverse racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds. The primary outcome for this study was the proportion of primary HPV screenings among all screenings performed. Secondary outcomes included patient and provider perception, knowledge, acceptance, and satisfaction. This study found that both arms achieved high uptake of primary HPV screening and there were no clinically significant differences in patient and provider satisfaction either. Near complete uptake of the new primary HPV screening recommendation was achieved.

The features making this a pragmatic trial include embedding the trial in routine care, using a real-world comparator, enrolling a broad, relevant population, and choosing outcomes with direct relevance to clinical practice and patient and provider acceptability. This study examined the effectiveness of screening test implementation strategies rather than the safety and efficacy of the HPV test itself, which is more of a concern in healthcare technology assessments. The study findings provide insight to other health systems on the implementation of guideline changes in clinical practice that are likely generalizable to other settings and even other screening tests. Further, the randomized prospective design overcomes numerous limitations of retrospective studies based on EHR and other RWD resources.

Conclusion

Pragmatic clinical trials offer a bridge between the rigor of randomization and the relevance of real-world evidence. For physicians, they represent an opportunity to generate practice-informed insights, improve patient care, and contribute to regulatory and policy decisions grounded in evidence that reflects everyday medicine. The integration of PCTs alongside explanatory RCTs and observational RWE is not a replacement but a necessary expansion of the evidence ecosystem.